February 22nd: Niki Lauda, James Hunt and the 1976 Formula One World Championship

Three-time Formula One world champion Niki Lauda was born today in 1949. Winning 25 races, and reaching the podium 51 times in 177 starts, the Austrian is an icon for F1 fans globally. Now non-executive chairman at Mercedes, and with similar roles previously at Ferrari and Jaguar, Lauda’s influence on F1 is enduring even after his racing career ended in 1985.

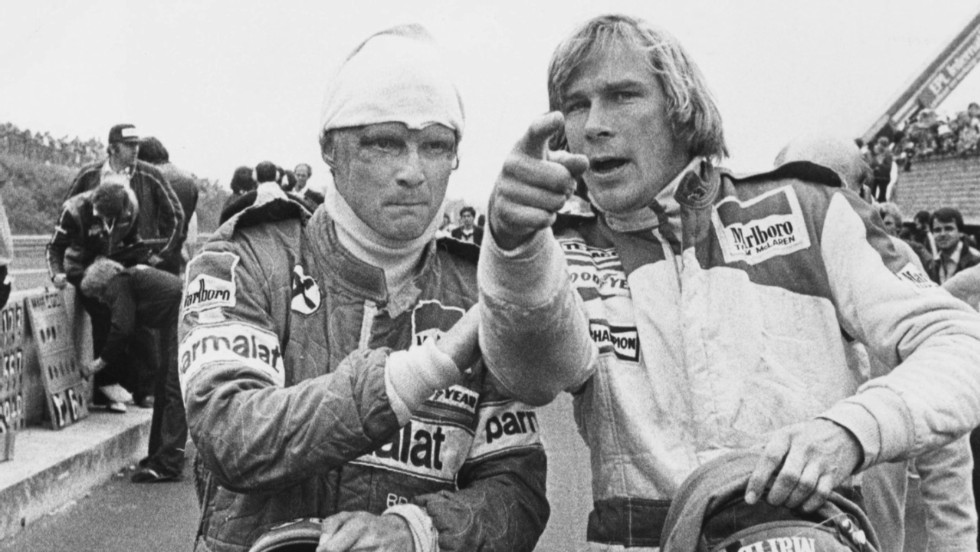

I’m going to use Lauda’s birthday today, however, as an excuse to write about one of the most romantic stories Formula One has to offer. The fierce rivalry between Niki Lauda and Briton, James Hunt, and the story of the 1976 world championship is worth telling time and time again. It is one I became aware of and grew to adore, after watching the recent film Rush - I can’t recommend it enough.

Lauda went into the

1976 season as the defending world champion. The Ferrari driver dominated the 1975

championship, standing on the podium eight times in fourteen races. Hunt

finished fourth in his Hesketh, winning in Holland, but suffering from five

consecutive retirements in the early season. Come 1976 the championship was

poised to be great before the chequered flag even dropped. The only car in

touching distance of the Ferrari’s for speed in 1975 was the Hesketh. The car

did lack, however, the reliability to be a championship-winner, even with Hunt

at the wheel.

Arguably, the car

was a reflection of those who built it and the man who drove it – sporadic,

unpredictable, unreliable, but, on its day, a world beater.

However, come 1976,

Hunt, realising his talent, yearned for the chance to mount a challenge against

Lauda’s Ferrari for the Championship – something he couldn’t do at the wheel of

the Hesketh. Surrounded by controversy, Hunt joined the McLaren works team to

take the fight to Ferrari and Lauda. Taking pole twice in as many races, and

then winning in Spain in round 4, Hunt had silenced his critics. But Hunt’s McLaren

lacked the consistency of Lauda’s Ferrari – the Austrian winning five of the

first nine races of the season.

The rivalry between

the two drivers grew more and more intense as the season went on; the British

Grand Prix set the mood for the rest of the season. Lauda in front (closely

followed by Hunt) suffered from a gearbox issue with 15 minutes left. Hunt, at

his home grand prix, seized the lead and crossed the finish line in first, but

his celebrations were short lived. Lauda and Ferrari, using its weight of

influence, appealed to the FIA on the grounds that Hunt had raced in the team’s

spare car. Hunt was disqualified, and Lauda awarded the victory. From here on

in, the race for the championship became a very personal affair.

The fact that the

drivers were such fundamentally different individuals made the rivalry all the

more endearing. The Austrian driver was a perfectionist, obsessing over every

inch of his Ferrari. Lauda’s eye for detail allowed him the extra horsepower

and/or downforce that led him to such success. His fanatical approach to the

car was reflected in how he drove. Reluctant to take unnecessary risk, Lauda’s

driving style was restrained and calculated. Hunt, by contrast, couldn’t have

been more different. The Briton drove racing cars how he lived life –

fantastically on the limit, with a do-or-die attitude that claimed so many

drivers of his era

The season-defining

moment came in Round 10 at the Nürburgring Nordschleife. A 14-mile-long stretch

of tarmac winding its way through the Eifel mountains, the ‘ring’ was the

deadliest race on the calendar. The narrow track was hugged by unforgiving

barriers either side, and beyond them, a wall of trees so thick that if a

driver came off at high speed the chances of survival were next to nil.

Before the race

began, with the rain pouring down, Lauda and several other drivers raised

concerns about the safety of the track. Despite qualifying on pole, it was in

Lauda’s interest to have the race cancelled, as it would have had effectively

secured him the driver’s championship. However, Hunt mustered enough support in

the drivers briefing room and the race went ahead as planned.

As it turns out,

Lauda had a right to be concerned. On just the second lap, Lauda veered off

track at high speed, as a result of a suspected suspension failure – the car piling

into the barriers and immediately setting itself alight. Moments later the

stricken Ferrari was hit by two other cars with Lauda still strapped inside,

burning alive. Miraculously, the Ferrari driver managed to escape the fiery

wreckage, and was quickly on his way to hospital fighting for his life. He

later fell into a coma. The race was restarted and Hunt eventually stood on top

of the podium.

The burns suffered has

left his face widely scarred; losing most of his right ear, the hair on the

right side of his head, his eyebrows and his eyelids. Remarkably, Lauda,

motivated to get back in the cockpit and to defend his title, refused extensive

reconstructive surgery. However, it was not the burns which made Lauda’s

condition so critical. He had inhaled potentially lethal poisonous fumes in the

medley, and required his lungs to be pumped. When recalling his accident, Lauda

thanked Hunt for keeping him alive; for without Hunt’s challenge for the

championship to motivate his recovery, he believes he would have died in that

hospital bed.

Astonishingly,

Lauda only missed two calendar races, and returned to F1 at Monza just six weeks

after the Nürburgring crash. He finished fourth, despite the immense pain caused

by his helmet chafing the open wounds on his face. Lauda wouldn’t win another

race for the rest of the season but still scored points. With Lauda not his

usual self behind the wheel, Hunt won consecutively in Canada and the United

States, which took the two drivers into the final race in Japan, with Lauda leading

Hunt by just three points.

Under the shadow of

Mount Fuji and just outside Tokyo, a soaking wet Fuji Speedway would host the

race to decide the driver’s championship and bring an end to such a gripping

Formula One season. Hunt qualified in second place, with Lauda right behind in

third. However, Lauda rightly voiced his concerns with regards to safety on

track well before the lights went out. Nonetheless, in the lashing rain, the

race went ahead, with fans poised to witness an epic finale to an epic season.

|

Unhappy with the

conditions, Lauda retired on the second lap – not risking a repeat of another

accident akin to what he had experienced in Germany. Things looked good for

Hunt. A master in the wet, and finally getting a good start off the line, the

Brit comfortably led the race in its early stages. But it was not plain

sailing. With eleven laps to go, Hunt began to suffer from tyre wear issues and

quickly passed by Depailler and Andretti. Nevertheless, if Hunt, now in third,

were to finish on the bottom step of the podium he would still be crowned

champion. Disaster then struck. Hunt suffered from a puncture, and was forced

to pit. Now in fifth, and with fewer and fewer laps remaining, it would take a

miracle for the Brit to catch the leaders and retake third place.

But that’s what he

did. Helped by the cars in front of him struggling for grip, Hunt, on a fresh

set of tyres, ragged his McLaren around the Fuji Speedway with a ferociousness

that sent the team pit wall into a state of trepidation. But Hunt had done it -

overtaking Jones and Regazzoni to retake third with just two laps to spare - Hunt

was crowned world champion and the scarred Lauda was runner-up.

After what would

turn out to be one of the greatest championships in F1 history, Lauda and Hunt

had developed a deep mutual respect for one another – maybe even the beginnings

of a friendship. Hunt celebrated in true Hunt fashion, with lots of alcohol,

cigarettes and girls. Lauda returned to his garage, meticulously tinkered with

his Ferrari, and prepared for pre-season testing.

The seasons after

his title-winning 1976 weren’t the same for Hunt; he wasn’t the same driver and

became troubled by his mind. He retired in 1979 and died fourteen years later

as a result of a heart attack. Lauda continued racing, winning a third world

title and then going onto retire in 1985.

However, before

Hunt’s untimely death, the two drivers crossed paths again. In the film Rush, Lauda recalls being distracted by

a tall, scruffy-looking blonde man, bumbling around London on a bicycle. It was

Hunt, but a shadow of his former self. Hunt had become troubled by alcohol

since his retirement from F1. Lauda chatted to his old foe, recalling memories

and updating one another on each other’s lives. Short of money at the time,

Lauda gifted Hunt some cash, and sent him on his way.

When he recalled

this meeting, Lauda felt sad. He had always respected Hunt, irrespective of

their differences on and off the track. But the Austrian wasn’t surprised. It

was how Hunt had always lived life; always on the very edge, an all-or-nothing

character – traits that made life after Formula One very difficult.

The Lauda-Hunt story is why us fans love F1. The

romance, the rivalry, the tiniest instances on track that can define a season.

Let’s hope the 2019 season can offer but half of what the 1976 Championship

did.

Daniel Whitaker.